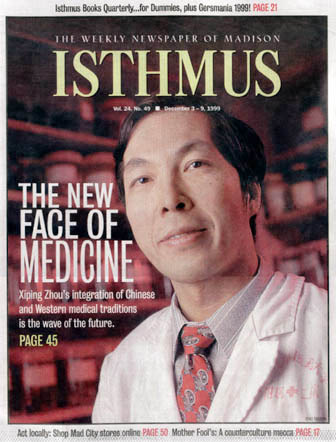

Xiping Zhou’s integration of Chinese and Western medical traditions is the wave of the future.

Published in Isthmus, the weekly newspaper of Madison, Wisconsin | Date: December 3, 1999 |

Written By Vesna Vuynovich Kovach | Photos: Eric Tadsen

Xiping Zhou, a practitioner of Chinese and Western medicine, is the first acupuncturist on staff at a Wisconsin hospital.

“Inhale,” says Dr. Zhou.

Between immaculately groomed fingertips, Zhou holds an acupuncture needle: a sharpened shaft of wire two inches long and six times thicker than a human hair. Half its length is fortified with a coil of wire, a tiny hilt. A triple O-loop of wire stands straight up from the top of the coil.

As if aiming a very small pool cue, Zhou cocks his hand back from the wrist once, twice, three times. “Exhale,” he says, then drives the needle one-quarter inch into the bare flesh of the small of the back of his patient, Gail Marker, who’s lying face down on a padded massage table.

The bangs of his short hair swept to one side of his forehead, Zhou rips open another five-needle blister pack of sterile, single-use needles. He walks around Marker, inserting more needles, sometimes stopping to adjust one, twirling it minutely and asking, “Feels okay?” Eventually, 15 needles bristle from Marker’s scalp, her back, her legs, her feet.

To six of the needles, Zhou attaches little alligator clips connected by wires to a six-volt battery. He adjusts knobs that control the intensity and the frequency. “Is that too much?” he asks.

“You can turn it up a little more,” Marker says.

“How’s that, okay?”

“Fine.”

“You’re sure? Okay, now you rest,” says Zhou. He shuts the door behind him, leaving Marker in the dimly lit room, with softly playing traditional Chinese music.

To a Western ear, this music isn’t easy: no repeating rhythmic figures or melody loops. Clearly, though, each note, isolated in its own long moment or else tumbling forth in part of a rich, cascading arpeggio, fits exactly in an ordered, if inapprehensible, pattern.

Chinese-born Xiping Zhou (pronounced “See-ping Joe”), 39 years old, is a master of traditional Chinese medicine, which, like the music, is ancient, complex, and, to the typical Westerner, unfathomable.

But unlike most acupuncturists in America, Zhou is a doctor of Western medicine as well–in China, he earned an OMD (Oriental Medical Doctor), a five-year degree which permits him to practice both types of medicine there. He’s a full professor at the Midwest College of Oriental Medicine in Racine (the only acupuncture school in the Midwest that can grant a master’s degree), and the founder of the American Alternative Healthcare Center, with branches in Madison and Milwaukee. He also teaches Tai Chi, meditation, acupressure, and massage through the UW-Extension and the UW Memorial Union.

This summer Zhou made state history when he joined the newly launched Integrative Medicine Program at the Columbia West Medical Clinic, part of Milwaukee’s Columbia-St. Mary’s Hospital. Becoming the first staff acupuncturist at a Wisconsin hospital is not just a personal coup for Zhou; it’s an example of how the walls between two formidable medical traditions are beginning to break down, if not exactly crumble.

“This is the way things are going to be,” predicts David Shapiro, the clinic’s regional director. Shapiro, who is an MD and a Fellow of the American College of Physicians, said that there were “some fairly skeptical physicians, and some heated discussions” when the project began. But the future lies in integrative care, he says.

“It’s now a question of, do you want to be viewed as an obstructionist, as ignorant? Or do you want to have an idea of what your patient is doing? These practices are popular with patients for some very good reasons, like, they work.”

Further proof that the public is serious about alternative medical traditions: though most approaches, including acupuncture, are not covered by insurance in most states, people are nevertheless willing to pay out of pocket for them. A recent survey reported in The Journal of the American Medical Association shows that Americans spent at least $27 billion on alternative therapies in 1997.

“This century, Western medicine has been going very good, with huge benefits for people’s health,” says Zhou. “New machines, powerful drugs. But it’s gone to some extremes. High-tech modern methods bring a lot of side effects: surgery causes harmful scars, drugs have side effects for the immune and digestive systems. And people want more individual attention. They want us to treat them as a person.”

“I don’t say everything Chinese is good. It’s a developing country, a very poor country. But it’s very advanced regarding medicine. They’re open minded; they use Western medicine a lot. You find big equipment–CAT scanners, MRI machines–used in conjunction with Chinese medicine. Western doctors work side by side with acupuncturists and herbal doctors. Chinese thinking is always yin and yang, two aspects. Positive, negative, always.”

Zhou now hopes to pass on this integrative approach to American students. In a few months, he will open the doors to his own school, the East-West Healing Arts Institute, at 1020 Regent Street. Depending on their field of study, graduates will qualify for national certification and/or state licensing in acupuncture, herbalism, or Western- or Eastern-style therapeutic bodywork.

“I am about synthesis,” says Zhou. “Bringing together East and West.”

In the main reception room of his Hilldale area clinic, Zhou, wearing a white lab coat over his deep purple velvet shirt, explains how he determines where to insert acupuncture needles. According to Chinese medical tradition, he says, a network of energy pathways–“meridians”–runs throughout the human body. Through stimulating certain points along these meridians, the flow of energy, or qi (pronounced “chee”) is enhanced, and the qualities of yin and yang (negative and positive) are brought into balance. “This is a very simplified explanation,” he says, “There is much more to it. Chinese medicine uses a whole different system for understanding the body.”

For instance, Zhou inserted Marker’s needles in points along her liver, bladder and gall bladder meridians. But these terms don’t refer to the organs we call by those names. “It’s kind of functional, the relationship between what Chinese call ‘liver’ and the anatomical liver. You can translate only about 80% between Eastern and Western terminology.”

What’s more, Marker, 53, is not here for liver, bladder or gall bladder complaints. Earlier this year, she lost feeling and function along the right side of her body, so that she had a hard time walking or using her right hand. And her physicians were unable to pinpoint the cause of her sudden disability.

“They checked for MS, stroke, Lou Gehrig’s disease, brain tumors–they said they’d never seen anything like it,” says Marker, after her needles are removed and Zhou has given her a full-body therapeutic massage. “They said my only option would be back surgery. But they couldn’t guarantee the outcome–it might even make things worse.

Marker, a program director with the Mental Health Center of Dane County, looked around for alternative treatments. “I thought, ‘Why not try acupuncture? What have I got to lose?’”

On her first visit, Zhou diagnosed Marker by placing his fingers on several points along her wrists to examine her pulse, inspecting her tongue and, importantly, asking questions about her appetite, her sleep and the stresses in her life. Through this holistic approach, traditional Chinese medicine healers can often pinpoint problems that confound Western medicine, says Zhou: “Western medicine treats the symptom. Chinese medicine treats the whole person–it looks at the big picture.”

Zhou framed a conclusion both in Eastern terms–“qi and blood stagnation”–and Western–“a degenerated disk between lumbar four and lumbar five.” It’s hard to imagine how two such incongruous descriptions could equate. Nevertheless, an independent MRI test confirmed his Western-style diagnosis. After 10 sessions, Marker’s symptoms are almost completely gone.

“The disk wasn’t getting the nutrients it needed,” says Zhou. “Circulation is better through those meridians that were blocked, so the disk was able to become more healthy. But don’t mention about the liver and gall bladder. It’ll just confuse people: ‘What does the liver have to do with a disk?’ Just say energy. Qi.”

When Xiping Zhou was just three months old, he began having seizures. He spent a month in the hospital, but the doctors there were unable to stop the attacks. The family turned to Zhou’s uncle, an acupuncturist who specialized in stroke recovery.

After a few sessions of acupuncture and herbal treatments, says Zhou, “the seizures just stopped. My uncle said it was a minor stroke. Later, neighbors told me they were surprised I was alive, and growing up healthy and normal.”

Through high school, Zhou helped out at his uncle’s clinic. “I saw so many people getting better. I decided to learn Chinese medicine, and to make stroke therapy my specialty, too.”

Zhou grew up in Qiqihar, an industrial center that produces locomotives and other heavy equipment. With a population of 1.4 million, it’s “a small city for China,” says Zhou, but crowded nevertheless.

In 1980, Zhou left Qiqihar to study at the Heilongjiang Medical University of Traditional Chinese Medicine in the provincial capital of Harbin. After graduation, Zhou joined the faculty, practicing medicine at one of the university’s three hospitals. Soon he became chief lecturer and vice director of the acupuncture department.

Zhou learned to read and speak English and often talked with Americans who were interning at the university. He found himself hooked on America. “I read some articles. I saw that the United States has some interest in acupuncture. I wanted to bring acupuncture knowledge to the West. To have more opportunities in the USA.”

While getting to the United States wouldn’t be easy, leaving China wasn’t the hard part–Zhou says the Chinese government is only concerned with high-profile defectors. The real obstacle proved to be the Immigration and Naturalization Service. “They won’t give visas” to Chinese citizens, says Zhou, unless the citizens have a good reason to visit–and a good reason to go back home.

In 1993, the university arranged for Zhou to lecture on scalp acupuncture, his speciality, at a three-day conference in Los Angeles. Unexpectedly, the visa he received was good for six months–the maximum length available. Zhou saw his chance to make a life in America.

But he knew that university officials would cancel his trip if they realized they were losing him for good. So Zhou told no one but his wife and mother that he meant to stay in the U.S. The family scraped together $400–four months of his salary. “My mom sewed it into my underwear,” he says.

After the conference, two Americans–the director of the conference and a Princeton, New Jersey acupuncturist whom Zhou had met as an intern in China–gave Zhou temporary work. “They took care of everything–food, house,” says Zhou. “We went to Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Baltimore, treating patients. I didn’t have to spend one penny,” Zhou recalls.

“For the first three months, I was very excited. See all American good life, everything here. Good! After three months, I got very depressed. Sending resumes, nobody responds.” Back in China, the hospital quit paying Zhou’s salary. Zhou’s wife and mother had worried about the plan from the start. Now, he says, “they were scared.”

Just days before his six months were up, Zhou landed a job at the Minnesota School for Acupuncture and Herbal Studies. “I never did touch that $400,” says Zhou.

Liping Mu, Zhou’s wife, joined him in Minnesota. Soon after, Zhou moved to Madison to teach at the Midwest College of Oriental Medicine, which had a State Street campus then. But it wasn’t until 1997 that Zhou and Mu were able to bring over their young son, Shengbo, who’s now seven and a half. “The students knew that I become crazy because my son cannot come here. When I told them I was going to China to pick him up, they were very excited for me. That was the first time I went back to China.” Zhou also brought back his mother, Shufeng Meng, from that trip.

Meng has been helping Zhou and Mu take care of their second child, 18-month-old Stanford. But she hopes to return to China soon after Mu completes her accounting studies at UW-Whitewater in December. Zhou will miss Meng–“she’s the best mom in the whole world,” he says–but he’s not a bit homesick for the weather in his native province, Heilongjiang, which borders on Siberia. It’s the northernmost province of China. “It’s six months winter, solid,” says Zhou. “Winter here in Wisconsin is very mild.”

Plus, after sharing a one-room apartment with up to seven other people all his life, Zhou likes owning his own home, a moderate-sized three-bedroom house off Cottage Grove Road. “In China, this is an impossible dream,” he says. “In Heilongjiang, only the governor has a house like this.”

In the years since Zhou’s arrival in the United States, acupuncture has needled its way into mainstream medicine. Says Steve Busalacchi, public relations director for the State Medical Society of Wisconsin: “We don’t even consider acupuncture to be ‘alternative.’” Physicians, he says, want scientific proof that something is effective– and the jury is now in on acupuncture.

“There’s been enough evidence by now,” says Busalacchi.

Congress authorized the National Institutes of Health in 1992 to establish the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine to “facilitate and conduct research” into “alternative medical treatment modalities” including acupuncture. Six years later, the NIH released its landmark “Consensus Statement” calling acupuncture “an effective treatment for nausea caused by cancer chemotherapy drugs, surgical anesthesia, and pregnancy; and for pain resulting from surgery and a variety of musculoskeletal conditions.” The statement also said that acupuncture may soon be clinically proven to have other uses as well.

In 1996, the Food and Drug Administration approved the use of acupuncture needles by licensed practitioners. Physicians who are licensed in acupuncture can practice it in all 50 states; licensed or certified non-physicians can practice acupuncture in 34 states and the District of Columbia. The NIH projects that in the year 2000, there will be 20,000 licensed acupuncture practitioners nationwide, twice as many as in 1998. And The Journal of the American Medical Association reports that 75 of the nation’s 125 medical schools offer courses in, about, or including information on complementary and alternative medicine.

Lately, hospitals around the country have launched Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) programs where doctors can refer patients to acupuncturists, chiropractors, or other practitioners. The Integrative Medicine Program where Zhou works is one thriving example; there’s already a second location with its own team of CAM practitioners. And this fall, Meriter Hospital started its Complementary Medicine Program.

Even outside of such programs, doctors increasingly refer patients to acupuncturists. Kae Ferber, a Dean Clinic physician specializing in geriatrics, recommends Zhou to patients suffering from chronic pain due to neuropathies, arthritis, and stroke.

“Acupuncture really helps pain,” she says. “It reduces inflammation and increases mobility. As a doctor, when you think about it, to relieve pain is one of the most important things you can do.”

Zhou’s Madison success stories are dramatic and many. Nelson George, 78, was completely wheelchair-bound from spinal stenosis before he started acupuncture treatment; now he can walk more than 100 yards with a walker. Linda Leese twisted her leg in July, but it wasn’t until she began acupuncture in mid-October that the pain, swelling, and stiffness went down. And Jackquie Schwoerer says acupuncture is relieving her chronic shoulder pain of seven years.

But Zhou says Chinese medicine is “really beyond needles” and “beyond pain.” He uses acupuncture to treat conditions not specified in the NIH report, including type 2 diabetes, thyroid imbalances, hormonal problems, irritable bowel syndrome, depression, and more.

Helen Wheeler, for instance, found relief from chronic bronchitis, for which she was taking seven different medications. “When Dr. Zhou put that needle in my throat, it was like somebody turning a key,” she says. Her “terrible, continuous” cough was gone within two weeks, and she’s been off the meds since June. Nevertheless, acupuncture is not sanctioned by Western practitioners as a treatment for bronchitis.

Audrey Robertson’s case is even more controversial. Trying to conceive a second child, she and her husband visited doctors for five years of fertility tests and treatments. Robertson underwent biopsies and a hysterosalpingogram, in which her fallopian tubes were dyed for x-ray observation. She had corrective surgery. She took fertility drugs and tried two different kinds of artificial insemination. Then she stopped taking the drugs and turned to acupuncture and herbal treatments with Dr. Zhou. Two months later, she was pregnant. Last month she gave birth to Jillian Grace, 8 pounds, 8 ounces.

“I’ve never felt more healthy,” says Robertson. “I firmly believe that this is good. It’s natural. Deep down, I think it was the diet and the Chinese herbs that worked for me. Dr. Zhou says if the system is out of balance, it can’t sustain another being.”

Did Dr. Zhou’s treatment help Robertson get pregnant? “I can’t really comment on this at all,” says Dr. Omid Khorram, an infertility specialist at UW Health, who administered some of Robertson’s artificial inseminations. “I don’t know how it works. I’ve heard plenty of anecdotal cases, but I’m not aware of any studies published in Western journals showing the effects of these treatments in this area.”

Dr. Richard Roberts is even more cautious. “It’s a powerful anecdote, but from a scientific standpoint, [Robertson] might have become pregnant in the sixth year anyway,” he says. “It’s like the couple who tries to conceive for seven years, then decides to adopt and gets pregnant three months later.”

A professor of family medicine at the UW Medical School, Roberts sat on early panels that led to the influential 1998 NIH Consensus Statement. “Acupuncture is something I do recommend, in limited situations, like for chronic pain.” But, he says, “Herbs are a great unknown. The Chinese herbs may have had the same hormonal effects as the fertility drugs–we don’t know.” Roberts doesn’t buy the idea that herbs are safe because they’re natural. “If something’s strong enough to help, it’s strong enough to hurt.”

Though Zhou is now reconciled with his former university (his former colleagues honored him in 1997 with the title Long-Term Professor), he has no plans to return to China.

Pending an okay from the state Educational Approval Board, the East-West Healing Arts Institute will open early next year. The school will train students in three main disciplines: massage therapy, herbalism, and acupuncture.

Graduates of the Eastern massage, herbalism, and acupuncture programs will be eligible to earn professional credentials by taking exams administered by the National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (NCCAOM) in Alexandria, Virginia. Massage graduates and acupuncture graduates can apply for a state of Wisconsin license (No state license is needed to practice herbalism). Zhou hopes the institute will eventually confer master’s degrees.

The school will roll out one department each year during its first three years. First will come the massage training program, which Zhou says will be unique in the Midwest, with separate, full-fledged Eastern and Western tracks. Grads from either track can apply for the NCTMB, which stands for Nationally Certified in Therapeutic Massage and Bodywork.

Next year, Zhou will add an herbalism curriculum, with an online option for distance learning. The acupuncture department, scheduled to start in 2002, will be a three-year full time program.

Zhou says the institute will “combine traditional wisdom with modern science.” All students will learn anatomy, physiology, pathology and kinesiology, as well as alternative healing arts.

“I believe in working together with Western doctors,” says Zhou, noting that both Chinese and Western medical traditions have their limitations. “There’s nothing perfect in the world.”

The future lies with “integrative, complementary medicine,” he says. “That’s the 21st century tradition.”